Soil Conservation Districts

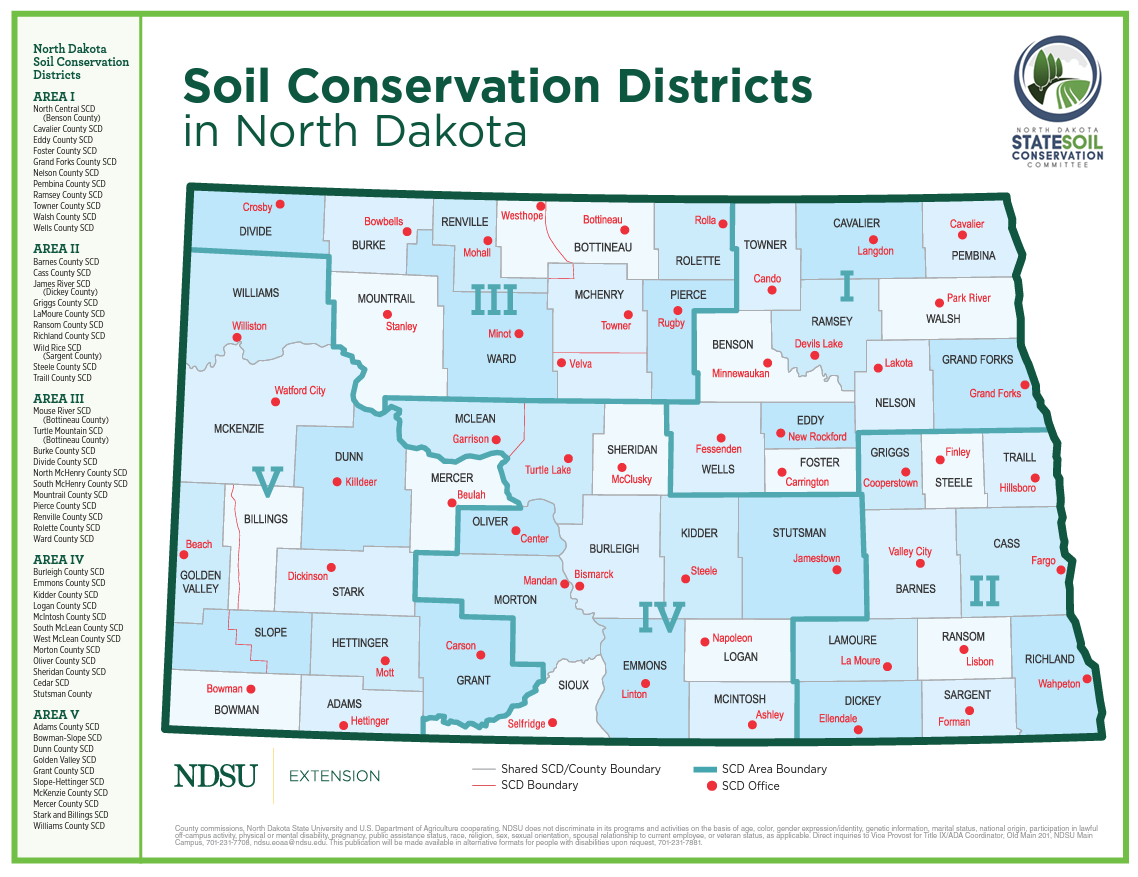

Soil Conservation Districts are crucial members of a three-way partnership of federal, state, and local agencies working toward soil and water conservation. In North Dakota, there are 54 districts, one in each county, organized into five areas.

- Area I - Benson, Cavalier, Eddy, Foster, Grand Forks, Nelson, Pembina, Ramsey, Towner, Walsh and Wells Counties.

- Area II - Barnes, Cass, Dickey, Griggs, LaMoure, Ransom, Richland, Sargent, Steele and Traill Counties.

- Area III - Bottineau, Burke, Divide, McHenry, Mountrail, Pierce, Renville, Rolette and Ward Counties.

- Area IV - Burleigh, Emmons, Kidder, Logan, McIntosh, McLean, Morton, Oliver, Sheridan, Sioux and Stutsman Counties.

- Area V - Adams, Billings, Bowman, Dunn, Golden Valley, Grant, Hettinger, McKenzie, Mercer, Stark, Slope and Williams Counties.

History of Soil Conservation

While soil conservation districts had their baptism by fire following the devastation of the 1930s Dust Bowl, the movement got its beginning decades earlier. It was championed by Hugh Hammond Bennett, a young college graduate who went to work as a soil surveyor for USDA in 1905.

Now recognized as the “father of soil conservation,” Bennett spent 20 years trying to bring attention to the nation’s eroded soils and the need for conservation. Lawmakers finally started to listen in the late 1920s, and the Dust Bowl — a drought that led to massive dust storms and topsoil losses across a swath of land reaching from Texas to Canada — fueled the movement.

The groundwork for the Dust Bowl was laid in the early 1900s when high demand for wheat, generous federal farm policies and a series of wet years caused a land boom in the Great Plains. New machinery made for easier and faster farming, and vast tracts of native grasslands in the Plains — more than 100 million acres — were plowed to plant crops, according to the USDA.

But the stock market crashed in 1929, and the Great Depression followed. Wheat prices plummeted, and farmers in the Plains plowed up even more land to try to recoup their losses. Prices dropped further, and drought conditions set in, causing widespread crop failure. Many farmers abandoned their fields to find work elsewhere, leaving behind a landscape that had changed from protective grassland to exposed soil.

The result was large dust storms that blew exposed soil as far as the East Coast. Bennett seized the opportunity to explain the cause of the dust storms to Congress and push for a permanent soil conservation agency. The Soil Conservation Service was created in 1935, and Bennett served as its first chief. Its predecessor, the temporary Soil Erosion Service — also led by Bennett — had established demonstration projects to show landowners the benefits of conservation. In 1994, Congress gave the Soil Conservation Service a new name: the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

As early as 1935, USDA managers began to search for ways to extend conservation assistance to more farmers, believing the solution was to establish democratically organized soil conservation districts to lead the conservation effort at the local level.

To that end, USDA drafted the Standard State Soil Conservation District Law, which President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent to the governors of all states in 1937. The first conservation district was organized in the Brown Creek watershed of North Carolina that same year.

Across the United States, nearly 3,000 conservation districts—almost one in every county— work directly with landowners to conserve and promote healthy soils, water, forests and wildlife. The National Association of Conservation Districts (NACD) represents these districts and the more than 17,000 citizens who serve on conservation district governing boards.

Conservation districts may go by different names—”soil and water conservation districts,” “resource conservation districts,” “natural resource districts” and “land conservation committees”—but they all share a single mission: to coordinate assistance from all available sources—public and private, local, state and federal—to develop locally-driven solutions to natural resources concerns.

In addition to serving as coordinators for conservation in the field, districts: • Implement farm, ranch and forestland conservation practices to protect soil productivity, water quality and quantity, air quality and wildlife habitat; • Conserve and restore wetlands, which purify water and provide habitat for birds, fish and other animals; • Protect groundwater resources; • Assist communities and homeowners in planting trees and other land cover to hold soil in place, clean the air, provide cover for wildlife, and beautify neighborhoods; • Help developers control soil erosion and protect water and air quality during construction; and • Reach out to communities and schools to teach the value of natural resources and encourage conservation efforts.

For more information view - YouTube – Hugh Hammond Bennett: The Story of America’s Private Lands Conservation Movement.

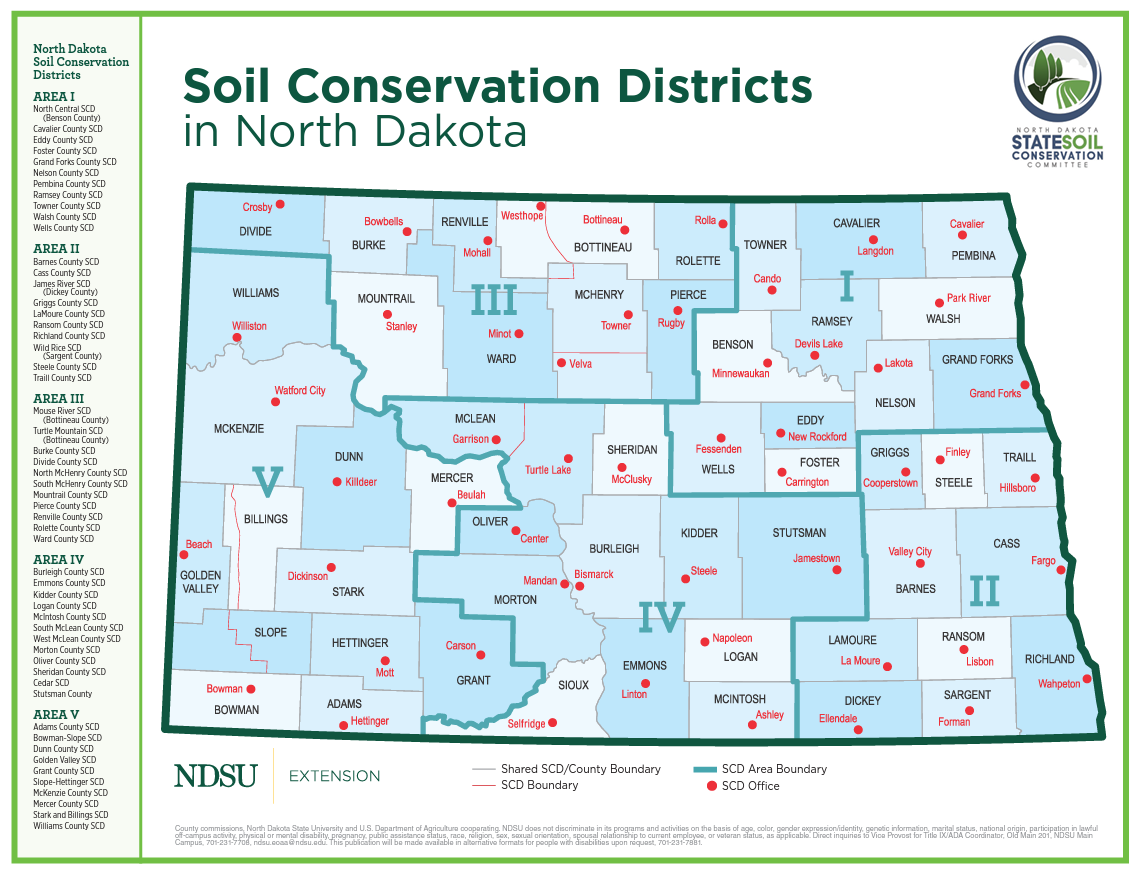

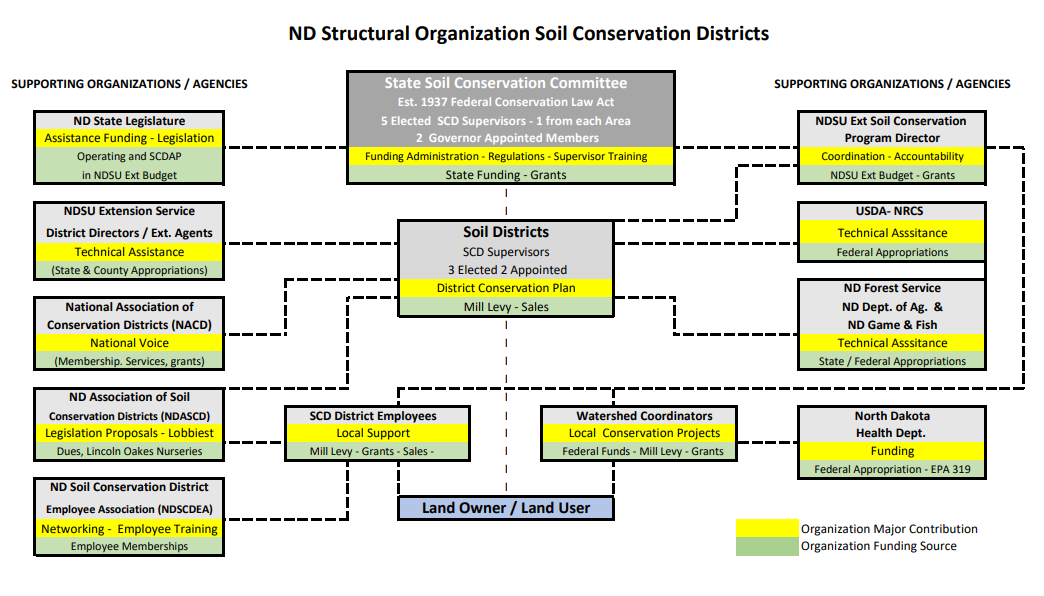

Structural Organization of Soil Conservation Districts

The Soil Conservation District is a crucial member of a three-way partnership of federal, state, and local agencies. The continuation of this working relationship is vital to the work of soil and water conservation. The partnering agencies in the above chart are integral working parts of a multi-agency team effort to protect and preserve natural resources.

Districts are generally organized in a similar manner. The board of supervisors provides overall supervison and sets policy assuring that the district performs tasks required by law and memorandums of understanding.

The everyday business of running a district is handled by the district staff. The district manager is responsible for handling administrative details and office operations on the board's behalf. Managers may also assume technical responsibilities. The district technician is responsible for providing technical support, plan reviews, etc. Each district employee reports to the board of supervisors and provides the board with information it needs to make policy and planning decisions.

Soil Conservation Planning

As stated in North Dakota Century Code (NDCC) 4.1-20-01, the purpose for the existence of the soil conservation districts is:

It is the policy of this state and within the scope of this chapter to provide for the conservation of the soil and soil resources of this state and for the control and prevention of soil erosion, and to preserve the state's natural resources, control floods, prevent impairment of dams and reservoirs, assist in maintaining the navigability of rivers, preserve wildlife, protect the tax base, protect public lands, and protect and promote the health, safety, and general welfare of the people of this state.

The district planning process is critical and should be completed utilizing the best data available. It should include the physical facts of the district such as, climatic and soil conditions, land use, size and type of agricultural practices, and resource problems. Also, it shall include suggestions for a program that will help correct the resource problems that exist. The NDCC Chapter 4.1-20-24.1(h) specifies what a plan must do:

“…plans must specify in such detail as may be possible the acts, procedures, performances, and avoidances that are necessary or desirable for the effectuation of those plans, including the specification of engineering operations, methods of cultivation, the growing of vegetation, cropping programs, tillage practices, and changes in use of land”

It is essential that district officials be thoroughly acquainted with resource problems, be able to evaluate their importance and be willing to take appropriate steps to solve these problems.

The planning process is an excellent opportunity for the board to bring in other agencies, groups, or individuals with interest and responsibilities in conservation to work together in planning and activating a dynamic conservation program that will benefit all. Districts may utilize trained facilitators to receive public input to assist in identifying and prioritizing conservation needs.

Districts may also want to partner with their local NRCS Agency to assess the natural resource concerns in their area by leading a Local Work Group (LWG). This locally led process helps identify resource concerns, priorities, and tools to address those needs. Representation includes individuals from state and federal agencies, agricultural and environmental organizations, Cooperative Extension, and local community members.

District Planning Process

After gathering data and public input, a plan shall be developed. This plan should include the items which will receive emphasis in the operation and education of the district. A broad-based goal shall be created for the district based on the resource needs and public input. To achieve the goal, the district shall complete a list of objectives that address the most pressing soil and water conservation problems. The final step in completing the planning process is creating specific tasks that detail the activities that will be carried out and ideas that will be promoted. Utilizing the S.M.A.R.T planning model each objective shall include:

✓ Specific What is the objective the district wants to achieve?

✓ Measurable How will the district measure achievement of the objective?

✓ Attainable What steps/tasks will be taken to achieve the objective?

✓ Realistic Does the district have the resources to achieve the task?

✓ Timely How long will it take to achieve the task?

As part of the implementation process, NDCC 4.1-20-24.1(h) requires districts to: “… publish such plans and information and bring them to the attention of occupiers of lands within the district.”

The conservation plan / plan of work should be reviewed monthly and revised as new resource concerns appear, new best management practices are developed, or as new information, such as more accurate soils surveys become available. The review of the plan should be made the first order of new business at every regular meeting.

Forming partnerships is critical to the success of a district’s plan. The district may consider entering into a Memorandum of Understanding with partners to detail expectations and activities that will lead to the accomplishment of tasks and objectives detailed in the plan. Potential partners include, but are not limited to:

• County Water Resource Board

• Municipalities

• North Dakota Game & Fish Department

• North Dakota Forest Service

• North Dakota Department of Environmental Quality

• USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

A template for the annual plan of work can be found in our Soil Conservation Google Drive.

Soil Conservation District Assistance Funds

The ND Legislature may appropriate state funds each session to help defray costs of the local soil conservation districts for conservation activities. These funds are used to cover salaries of SCD employees who plan and design local soil conservation projects. The State Soil Conservation Committee allocates the funds to the districts based on the data each district inputs on the ranking report in DART. NDSU Extension notifies each district of their funding allocation and reimburses them for salary expenditures each quarter after receiving their quarterly DART report.

District Activity Reporting Tool (DART)

The District Activity Reporting Tool (DART) has been developed with the input and support of the NDCDEA to have a uniform state-wide reporting tool. DART includes a set of assigned tasks that when completed will facilitate the collection of financial data for the purpose of ranking, planning and quarterly reporting that will standardize in total how the Soil Conservation District Assistance Program funds were used statewide.

District Audit and Financial Report

The district should arrange for the annual audit of the account of receipts and disbursements of their district as required by the Soil Conservation Districts Law (N.D.C.C. 4-1-20-22).

Due to the 55th Legislative Assembly, Soil Conservation Districts were added to the list of political subdivisions to be audited by the State Auditor. The law requires the State Auditor, a Certified Public Accountant, or a Licensed Public Accountant to audit the districts every two years (N.D.C.C. 54-10-14).

The State Auditor may in lieu of conducting an audit every two years, require an annual financial report from districts with less than $2,000,000 in annual receipts. Districts are required to complete the Annual Financial Report for the year by December 31. In addition, the State Auditor may:

- Make any additional examination or audit deemed necessary in addition to the annual report.

- Charge the political subdivision an amount equal to the fair value of the additional examination or audit and any other services rendered.

- Charge a political subdivision a set fee for the costs of reviewing the annual report.

Soil Conservation District Mill Levy Authority

Note: The following is a summary of state laws relating to Soil Conservation Districts and should not be considered legal advice. Contact your local State’s Attorney for any legal services your SCD requires.

The Legislative Assembly granted the Supervisors of North Dakota Soil Conservation Districts the authority to levy a tax, not exceeding 2.5 mills, for the payment of the expenses of the district, including mileage and other expenses of the supervisors, and technical, administrative, clerical, and other operating expenses. This authority is provided in the North Dakota Soil Conservation Districts Law, N.D.C.C. 4.1-20-24.

Upon filing a certified copy of the levy, the county auditor of each county in the district will extend the levy upon the tax list of the county for the current year against each description of real property lying both within the county and the district in the same manner and with the same effect as other taxes are extended. The county treasurer collects all taxes and turns the funds over to the soil conservation district on a monthly basis. According to a February 21, 1992 Attorney General opinion, "Soil conservation districts are taxing districts because they are authorized to levy taxes under North Dakota Century Code - N.D.C.C. Section 4.1-20-24.”

N.D.C.C. 57-02-01 says, “Municipality” or “taxing district” means a county, city, township, school district, water conservation or flood control district, Garrison Diversion Conservancy District, county park district, joint county park district, irrigation district, park district, rural fire protection district, or any other subdivision of the state empowered to levy taxes.

Therefore, soil conservation districts are also subject to Title 57 because they are subdivisions of the state and have the authority to levy taxes.

N.D.C.C. 57-15-31 provides the formula for determination of a levy. This determination is made by considering the estimated expenditures for the current fiscal year and the required reserve fund. The municipality may only levy for what is actually needed for the fiscal year. This process eliminates municipalities from creating a big “nest egg.”

N.D.C.C. 57-15-27 provides that a municipality authorized to levy taxes may include in its budget an interim fund. The interim fund is to be carried over to meet any requirements of the next fiscal year that may become due prior to the receipt of taxes in that fiscal year. The interim fund cannot be in excess of what may be reasonably required to finance the municipality for the first nine months of the next fiscal year. The interim fund cannot exceed three fourths of the current appropriation for all purposes other than debt retirement and appropriations from bond sources.

N.D.C.C. 57-15 entitled “Tax Levies and Limitations.” N.D.C.C. 57-15-02 provides for the determination of rate:

Determination of rate. The tax rate of all taxes, except taxes the rate of which is fixed by law, must be calculated and fixed by the county auditor within the limitations prescribed by statute. If any municipality levies a greater amount than the prescribed maximum legal rate of levy will produce, the county auditor shall extend only such amount of tax as the prescribed maximum legal rate of levy will produce. The rate must be based and computed on the taxable valuation of taxable property in the municipality or district levying the tax. The rate of all taxes must be calculated by the county auditor in mills, tenths, and hundredths of mills.

The county auditor can limit the soil conservation district mill levy request and will only extend the amount of levy as allowed pursuant to title 57. The county auditor will not extend any levy in excess of the allowable levy which is the difference between the sum of the estimated expenditures, and interim fund needs and debt retirement and the sum of the projected revenues and cash balances. Allowance may be made for a permanent delinquency or loss in tax collection not to exceed five percent of the levy. N.D.C.C. 57-15-31.

Additional Mills – The ability of a Soil Conservation District to levy additional taxes, beyond 2.5 mills, with the approval of a majority vote of district residents is allowed under N.D.C.C. 57-15-01.1(4), (5). Districts wishing to do so should work with their local State’s Attorney.

Preliminary Budgets - In 2017, the North Dakota Legislature made some important changes to budget deadlines and the notice process, which the county and other local governments need to comply with every year. All local governments need to file a preliminary budget with the County Auditor’s Office. County Auditors will provide information on submitting budgets and mill levy requests. Filing dates are typically in early August.

Whether you are a county, city, park district, school district, township, fire district, or soil conservation district you will need to file a preliminary budget with the County Auditor. If you fail to file the preliminary budget by August 10th, you will be limited to levying the same dollars as levied in the previous year. You also must file a final budget to actually levy taxes for your budget.

When you provide the preliminary information to the County Auditor, you also need to provide the date, time, and place of your budget hearing, if you levy over $100,000 in taxes. The hearing date cannot be any earlier than September 7th nor later than October 7th. The reason for the deadline is to allow the county time to prepare an Estimated Tax Statement that needs to be mailed by the end of August. (N.D.C.C. 40-40-06(1))

If you levy over $100,000 in taxes, the County Auditors will put the hearing notice on the Estimated Tax Statement. If you levy less than $100,000, you will need to publish the notice of the budget hearing in your official newspaper six days prior to the meeting. (N.D.C.C. 40-40-06(2))

Once you have held your final budget hearing and your board has approved the current year budget, you will need to file your final budget with the County Auditor. Remember the amount requested for the final budget cannot be greater than the amount of your preliminary budget. (N.D.C.C. 40-40-10)

NOTE: Check with your County Auditor each year for budget hearing dates and deadline for the last day the board can make any changes and date for approval of the budget.